Empty homes wasted potential

The state of vacant properties across the UK

Across towns, suburbs and coastal villages in the UK, rows of silent houses and boarded terraces tell a story that sits awkwardly alongside headlines about housing shortages, rising rents and people sleeping rough. Empty properties are at once a symptom and a cause: they can signal market failure, ownership disputes, structural decline or seasonal patterns; they also represent an avoidable loss of housing supply, community decline and a drain on public resources. This article examines the most recent national pictures for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, explains the different causes that feed vacancy, reviews the policy and legal tools available to bring properties back into use, and proposes practical recommendations for local and national policymakers.

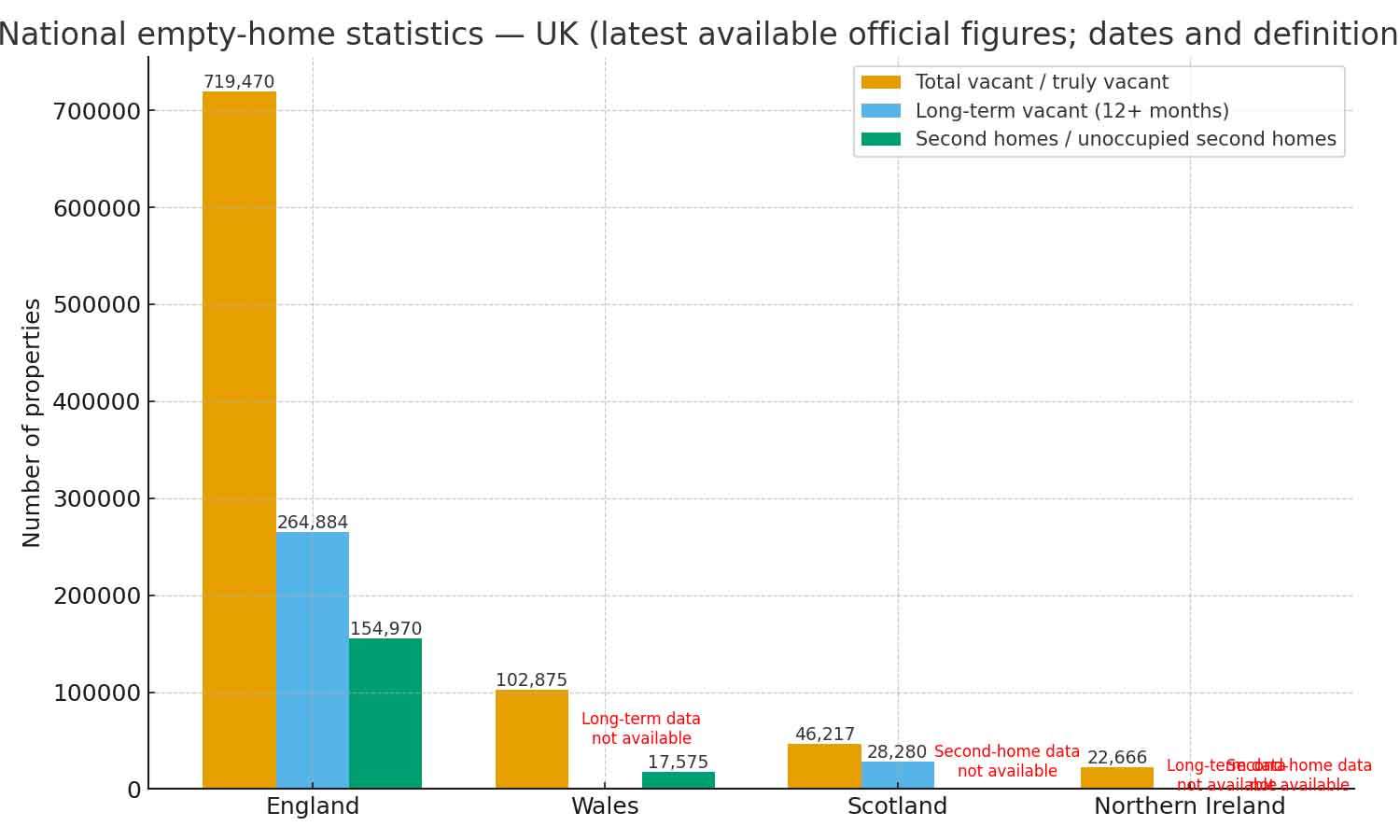

Where possible, the latest official statistics are used and the differences in definitions and collection methods between the four nations are made explicit. The headline numbers are stark: the most recent national estimates show hundreds of thousands of vacant dwellings across the UK, and tens of thousands that have been empty for a year or longer. Framing the problem clearly is important because policy responses must be targeted — the empty Victorian terrace in a former mill town requires a different fix to an unlet holiday cottage on a coastal headland.

What counts as an “empty home”?

Before diving into the numbers, a brief explainer. Different organisations and governments define an “empty” property in slightly different ways. Broadly, three categories are useful:

- Short-term vacant — homes temporarily unoccupied between tenancies or during refurbishment (a few weeks to a few months). These properties are generally part of a healthy housing market and do not usually cause long-term harm.

- Long-term empty — homes unoccupied for 12 months or longer. These are the focus of most policy concern. Many long-term empties are in poor condition, tied up in legal disputes or simply left unused by owners who have better financial returns elsewhere.

- Second/holiday homes — dwellings that are unoccupied for much of the year because they are used as second homes or short-term holiday lets. While not “empty” in the sense of dereliction, concentrations of second homes can have the same negative effects on local housing supply and community cohesion.

Statistics published by national government bodies, local authorities and charities sometimes combine or separate these categories in different ways. When quoting figures it is therefore important to identify the source and the date: the Office for National Statistics, national governments and land/property registries each collect vacancy information differently, and these differences affect comparisons.

The headline numbers — the national picture

England

The most recent national dwelling stock estimates for England indicate a very large number of vacant properties. On one widely used reporting date, there were in the order of hundreds of thousands of vacant dwellings across England, with a substantial share categorised as long-term empties (those vacant for 12 months or more). Long-term vacancies have risen in recent years in many parts of the country.

These are not merely statistical curiosities. With the affordability crisis biting and social housing waiting lists lengthening, long-term unoccupied homes present a tangible opportunity: refurbish and re-let them and supply could increase without building on greenfield land. But large numbers clustered in particular neighbourhoods can also entrench decline — boarded houses attract antisocial behaviour, lower neighbouring property values, and drain local authority enforcement resources.

Wales

The picture in Wales differs in scale and pattern. Census and dwelling stock reporting shows a significant number of unoccupied dwellings, and a notable element of the Welsh vacancy challenge is the prevalence of second homes and holiday lets in coastal and national-park communities. Census data identified many thousands of unoccupied dwellings in Wales, and the distribution is uneven: some rural and coastal local authorities face particularly high proportions of second homes, with consequent affordability pressures for local residents.

Local authorities in Wales actively collect and publish dwelling stock estimates and run targeted empty-homes teams. The challenge here is often to strike a balance between a valuable tourism economy and protecting year-round communities from displacement.

Scotland

Scotland’s official statistics report tens of thousands of empty homes, including a significant number that are long-term vacant. Scotland has, in recent years, engaged in a policy debate about second homes and their impact on fragile rural communities and islands; some local authorities have used discretionary council tax premiums and other measures to discourage long-term disuse and excessive second-home ownership. Scotland also monitors derelict and vacant land, which interacts with the empty homes problem in places where whole streets or blocks are affected.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland uses different administrative data sources for property counts and has its own distinct market dynamics. Recent reporting indicates several tens of thousands of vacant domestic properties. In many cases the drivers mirror those elsewhere in the UK: structural disrepair, ownership and probate issues, and low local demand in particular post-industrial towns. Because of Northern Ireland’s smaller scale and different tenure mix, localised interventions — often led by councils — are central to the response.

Why homes become empty: a mixed set of causes

Understanding causation is crucial for designing effective interventions. There is no single reason why a property lies empty for long periods; the root causes are diverse and typically interact.

1. Market and economic factors

Properties can remain unsold or unlet in weak housing markets. Where demand is low and repair costs are high, owners may prefer to leave a property empty rather than invest in expensive refurbishment that may not be recouped on resale or rent. Economic downturns, changes in local employment patterns, and the decline of traditional industries (manufacturing, mining) can leave whole communities with a surplus of poor-condition housing and little immediate demand.

2. Probate and legal issues

When an owner dies, property often becomes tied up in probate, wills or disputes between family members. These legal processes can be lengthy, and a house may remain unused throughout. Inheritance disputes, missing heirs and unclear title deeds all slow down the return of a property to active use.

3. Structural condition and contamination

Some properties require substantial work to be made habitable. Older properties with major repair needs — including structural problems, damp, asbestos, or contamination issues — can be expensive to adapt. Where expected refurbishment costs exceed market values, the commercial incentive to invest is weak.

4. Perverse incentives and tax treatment

Historically, low council tax or weak enforcement may have reduced the financial pressure on owners to bring empty properties back into use. Conversely, rising property values have encouraged some owners to hold vacant assets for future sale or development rather than renting them. Policy changes in recent years have sought to recalibrate incentives, introducing premiums and penalties for persistent vacancy in some parts of the UK.

5. Second homes and short-term lets

In many rural and coastal communities, the growth of second-home ownership and short-term holiday lets has tightened the market for year-round accommodation. Even where a second home is well maintained, it effectively removes housing supply from the local market for much of the year. Clusters of such properties can hollow out village life, reduce school rolls and alter the viability of local services.

6. Speculation and investment strategies

In particular markets, buy-to-leave strategies — where investors purchase properties in the expectation of capital appreciation but do not occupy them — can create long-term vacancy. While less visible than derelict houses, this behaviour contributes to regional shortages.

Consequences: costs to communities and services

Empty properties carry costs that go beyond lost housing supply. The impacts are local, tangible and sometimes long-lasting.

- Community decline and blight: Long-term vacant houses can fall into disrepair, become targets for vandalism and arson, and depress neighbouring property values. Streets with multiple empties often lose footfall and local commerce.

- Public sector costs: Local authorities expend staff time and limited budgets on tracing owners, serving notices and undertaking emergency repairs. Where properties become hazardous, councils may have to step in, temporarily securing buildings or carrying out remedial work.

- Reduced housing options: In places where permanently vacant properties are numerous, particularly in areas of high housing demand, the opportunity cost is high: homes that could provide affordable housing remain unused while families are in temporary accommodation or on long waiting lists.

- Safety and health risks: Derelict properties can become havens for vermin, mould and other hazards. They can also present safety risks where dilapidation leads to structural failure.

- Inequality and place-based tension: Concentrations of second homes and holiday lets are often blamed for rising local prices and the displacement of long-term residents, feeding political tensions.

What governments and councils can (and do) do: the policy toolkit

All four nations and numerous local authorities have a mix of legal, fiscal and practical tools to address empty homes. The evidence suggests that a combination of carrots and sticks — support and incentives coupled with enforcement where necessary — is the most effective approach.

Council tax premiums and local fiscal tools

One of the most visible recent changes in policy has been the expansion of council tax premiums on long-term empty properties and second homes. Local authorities in different parts of the UK have discretionary powers to apply a multiplier (or premium) to the council tax bill for properties that have been left empty for a defined period or are used as second homes. The size of the premium and the qualifying period (for example, properties empty for two years or more) vary by council.

The premium works both as a disincentive and as a revenue-raising mechanism; the additional income can be recycled into empty-homes programmes, grants for refurbishment, or local housing initiatives. Where premiums are set carefully, they nudge owners toward re-letting or sale without immediately resorting to heavy-handed enforcement.

Grants, loans and refurbishment assistance

Many councils operate empty-homes teams that provide practical help to owners. This can include technical advice, assistance with planning and building regulations, access to low-interest loans or discretionary grants for repair and retrofit, and support to find letting agents or housing association partners. The aim is to remove practical and financial barriers to bringing properties back into use.

Where owners are elderly, incapacitated or otherwise unable to manage refurbishment themselves, councils sometimes partner with housing associations or developers to acquire and refurbish properties for affordable housing.

Enforcement: EDMOs, compulsory purchase and demolition

Where engagement fails, local authorities have statutory enforcement powers. In England, the Empty Dwelling Management Order (EDMO) regime — rooted in the Housing Act 2004 — allows councils to secure the use of long-term empty properties for letting. In practice, EDMOs are rarely used: they are operationally complex, involve legal steps and are generally reserved as a last resort.

Compulsory purchase is another tool, used in extreme cases where long-term empties are part of serious neighbourhood decline and other interventions have failed. Compulsory purchase powers enable a public body to acquire property without the owner’s consent, but they carry high administrative and legal costs and are used sparingly.

Demolition is sometimes employed where buildings are dangerous or where whole streets are in such disrepair that rebuilding provides the best outcome. However, demolition is costly and removes housing stock, so it is seldom the preferred option.

Partnerships and innovative programmes

Partnerships with housing associations, social enterprises and charities often produce the most durable results. A successful approach is when councils identify clusters of empty homes and match them with refurbishment funding, social landlords, or community-led housing groups. These projects can deliver affordable homes while also improving neighbourhood appearance and vitality.

Moreover, targeted programmes that combine capital funding with wraparound support (project management, marketing, tenancy support) have a higher success rate than one-off grants. These comprehensive programmes address not just the physical refurbishment but also the practical challenges of finding tenants and sustaining tenancies.

Nation-by-nation detail and policy nuance

England: scale, EDMOs and local responses

England’s large housing stock means the absolute number of empty homes is high. Recent national dwelling stock estimates show a very large number of vacant dwellings, with long-term empties running into the hundreds of thousands. The English policy framework includes EDMOs, council tax premiums and a patchwork of local programmes funded by councils and occasional central government initiatives.

The use of EDMOs in England has historically been limited. Councils cite legal complexity, the administrative burden of managing properties brought back into use, and the ability to achieve better outcomes through negotiation and partnership. Consequently, most English councils prioritise targeted grants, loans and brokered solutions with housing associations.

Homes England and other national bodies have, at times, offered funding streams to support refurbishment of empty homes where the strategic case is strong. Local intelligence is key: mapping hotspots and focusing on clusters can convert several empties into multiple new homes at marginal cost compared with building afresh.

Wales: second homes, community balance and targeted action

In Wales, the prevalence of second homes in certain coastal and national-park communities is a defining feature. Census data revealed many thousands of unoccupied dwellings, and local authorities have been more active in both collecting data and developing local empty-homes strategies. Welsh policy levers include council tax premiums, empty-homes teams, and selective financial assistance for refurbishment.

Many Welsh councils adopt a place-based approach that recognises the role of tourism while seeking to retain year-round residents. This can mean offering refurbishment grants to convert derelict properties into permanently affordable homes or using additional council tax revenues to invest in community services.

Scotland: second-home debate and innovative local measures

Scotland’s policy conversation has placed a strong emphasis on tackling concentrations of second homes in fragile rural communities. The Scottish Government and some local authorities have explored higher council tax premiums and other measures to discourage leaving homes empty for most of the year. Scotland also has a well-developed network of third-sector partners and local authorities that bring empty properties back into use through targeted schemes.

The policy debate in Scotland is often framed around community sustainability: in island and remote communities, a single empty property can have an outsized impact on service viability, and therefore the response is frequently more interventionist.

Northern Ireland: different data, similar problems

Northern Ireland reports vacancy using administrative registers that differ from Great Britain, but the underlying drivers are comparable: market weakness in particular towns, probate and legal entanglements, and higher repair costs than market values justify. Local authorities in Northern Ireland lead much of the practical response, with programmes that combine enforcement with offers of assistance. Given the scale and localised nature of the challenge, partnership working is central.

Effective practice: what works on the ground

A review of successful programmes and case studies across the UK highlights a few common features:

- Accurate local data and hotspot mapping: councils that maintain up-to-date registers of empties and that map clusters can target resources more effectively. Empty properties concentrated in a few streets are more tractable than single scattered cases.

- Early engagement and tailored support: many properties are brought back by relatively low-cost interventions — clearing rubbish, minor repairs, or mediation with owners. Early, personalised engagement reduces the timescale for return to use.

- Financial support tied to outcomes: low-interest loans and targeted grants can unlock refurbishment where owners lack capital. Tying support to clear milestones and ensuring tenures that protect affordability for the long term increases public value.

- Partnership delivery models: local authorities working with housing associations, builders’ co-operatives, and community-led housing organisations deliver efficient conversions and secure long-term tenancies.

- Selective enforcement: enforcement powers — EDMOs, compulsory purchase — are most effective when signalled as credible alternatives to negotiation. Where used, they should be applied transparently with clear public benefit.

- Reuse for social housing and specialist accommodation: where possible, vacant stock has been recycled into affordable homes, temporary accommodation for homeless households, or supported housing, delivering social benefits and preventing further decline.

Risks and limits of policy

Despite the toolkit, there are limits. Enforcement is expensive and legally complex; compulsory purchase and EDMO use can be prolonged and contentious. Heavy-handed policies risk disincentivising owners from engaging. Council tax premiums are useful, but if set too high without clear alternatives, they can push owners into selling at a loss or fuel resentment in communities reliant on second-home income. In fragile towns, the root cause may be weak local economies; tackling vacancy without broader regeneration risks returning to the same problem in a few years.

Moreover, bringing a property back into use is just the first step: ensuring decent standards, sustainability (heat, insulation) and long-term tenancy stability requires ongoing investment.

Recommendations: a pragmatic national and local agenda

The following recommendations bring together evidence from successful programmes and the policy levers available.

For national government (and devolved administrations)

- Sustain targeted capital funding for local empty-homes conversion programmes, conditional on outcomes (number of homes delivered, length of tenancies, affordability safeguards).

- Clarify guidance and lower legal barriers for councils seeking to use enforcement powers, while protecting due process for owners.

- Support information-sharing and best practice by funding national empty-homes partnerships and toolkits that local authorities and third-sector partners can use.

- Use fiscal levers wisely: encourage discretionary council tax premiums on long-term empties and second homes but accompany premiums with transparent use of revenue to support local housing supply.

- Incentivise retrofit and refurbishment to net-zero standards by making grants or low-interest loans available for energy efficiency upgrades as part of empty-home conversion programmes.

For local authorities and housing partnerships

- Map empties and prioritise hotspots: concentrate resources where several empties can be brought back to produce measurable neighbourhood improvements.

- Offer tailored engagement: combine practical assistance, mediation, and finance to remove barriers for owners who want to act but lack capability or capital.

- Develop partnership delivery models with housing associations and community groups to manage refurbishment and let properties as affordable housing.

- Use enforcement strategically: ensure enforcement powers are credible but proportionate, reserved for cases where negotiated solutions have failed.

- Measure and report impact: publish local empty-homes figures regularly and report outcomes (homes brought back into use, public money spent, tenancies sustained).

For communities and the third sector

- Form community housing groups where possible to take on and refurbish multiple empties, using local knowledge and volunteer capacity to add value.

- Advocate for local policy balance that protects year-round communities while recognising the economic contribution of tourism where appropriate.

- Support vulnerable owners — older homeowners or those with health challenges — by providing advice and linking them to services that can help with disposal or management of empty properties.

Case vignettes: small actions, big returns

A few illustrative examples show how targeted action can turn a local eyesore into useful homes:

- In a post-industrial town, a cluster of Victorian terraces had been empty for years because refurbishment costs deterred individual owners. The local council mapped the cluster, brokered a deal with a housing association and secured a modest refurbishment grant. Within 18 months several houses were returned to use as affordable rented homes, stabilising the street and bringing footfall back to nearby shops.

- In a coastal village, a council introduced a council tax premium for second homes and ploughed the additional income into a community housing fund. That fund provided match funding to a community land trust that acquired and converted one empty property each year into a permanently affordable home for local people.

- A partnership between a county council and a charity specialising in empty homes created a small revolving loan fund to help owners with medium-scale repairs. By packaging loans with project management support, the programme unlocked dozens of homes that had stood empty because owners could not handle the practical complexity of refurbishment.

Conclusion: making the most of what we already have

Empty properties are, at root, a problem of misused resources: housing that could shelter families stands idle, often in places where demand is acute. The solution is not a single national policy, but a set of targeted, locally informed actions: accurate data to identify the problem, practical support and finance to unblock refurbishment, strategic use of enforcement to deter willful neglect, and partnerships to deliver sustainable tenancies.

In many places, the potential to convert existing vacant stock into secure, well-managed homes offers a faster, greener and more locally sensitive route to increasing supply than large-scale new-building alone. It also restores streets, revitalises communities and makes better use of public money. The challenge for policymakers and practitioners is to combine incentives that encourage owners to act with credible enforcement where necessary, to invest in the capacity of councils and third-sector partners to deliver, and to tailor approaches to the local reality — whether that is a seaside resort with too many holiday lets or a former mining town with a stock of ageing terraces in need of repair.

Bringing empty homes back to life is practical, often cost-effective, and politically popular. For communities across the UK, it is a tangible way of turning a problem into opportunity and ensuring that the bricks and mortar already in place work for people who need them most.